What is Transformative Economic Development?

A new periodic post about economic development from Greater New Orleans, Inc. President & CEO Michael Hecht. Inspired by questions about what economic development is, why it matters, and how it can have systemic positive impact, “Transformative Economic Development” is a handbook of best practices that can be used by anyone that wants to help create a thriving economy, and an excellent quality of life, for everyone in their community.

July 26, 2022 – In Chapter One, I wrote that “the essence of economic development is creating the conditions where businesses want to invest and where people want to live.” More often than not, public policy is how we achieve these conditions. At GNO, Inc. we are obsessed with public policy—it’s how we drive systemic transformation in business and social conditions, and “change the game” of economic development.

In its simplest form, public policy is “whatever governments choose to do or not to do.” This includes the laws, investments, initiatives, and other actions of local, state, and federal governments. A single new policy potentially affects everyone within the jurisdiction – that is, it is systemically impactful. So, from an efficiency and impact standpoint – positive or negative – public policy is where it’s at.

Examples of public policy that are relevant to economic development include:

- Tax laws

- Economic development incentives

- Infrastructure priorities

- Education and workforce policy

- Energy policy

- Innovation initiatives, like investment funds

- “Social Good” issues, like broadband access

- Quality-of-life initiatives, like public parks

- Any other law or initiative of the government that could positively or negatively impact a business’s decision to invest in, or an individual’s decision to live in, your community

If you get it right, public policy can create tremendous positive momentum. A good example is the zero-personal-income-tax policy of Texas, which has figured prominently in the “business friendly” brand of Texas, and is an oft-cited reason for businesses and people to move there. Just google “why is Texas business friendly” and see what comes up.

Of course, bad public policy can have tremendous negative impact. For example, the Biggert-Waters “reform” legislation of 2012 was meant to improve the National Flood Insurance Program, but led to the unintended consequence of millions of Americans being priced out of the program. (A national coalition led by GNO, Inc. was able to reverse the bad legislation. See www.csfi.info for more.)

Pro Tip: For organizations, nothing drives interest and relevance like public policy. It is so much better than a golf tournament.

So, just how does a policy become law of the land? For perhaps the best tutorial of all time, I recommend School House Rock. For those of you reading this during a meeting and unable to watch the story of how Bill becomes a Law, I’ve included throughout this chapter a good case study based on tax reform in Louisiana.

Tax Reform Case Study - Introduction

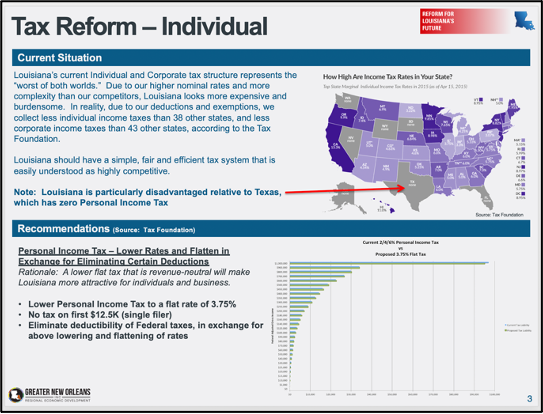

In 2021, GNO, Inc. led a successful effort to pass a constitutional amendment that lowered personal income tax in Louisiana from 6.0% to 4.25%. This took Louisiana from the 25th to the 4th lowest income tax state in the U.S. among those states that charge income tax. The amendment passed 54% to 46%, in what the Wall Street Journal emphatically called “Louisiana’s Tax Reform Breakthrough.”

Though we celebrated in 2021, the reform process had started many years prior, culminating when COVID threw the problems with our old tax system into stark relief.

Step 1: Problem Identification

Public Policy starts with problem identification. Here at GNO, Inc., we learn about our region’s problems via multiple channels: rankings and reports, the media, our board, our investors, etc. Anecdotal information typically comes out first, and is subsequently backed up and parsed with hard data and analysis by staff. The GNO, Inc. Public Policy Committee vets these problems, and sends them to the Executive Committee for further review and prioritizing.

Tax Reform Case Study - Problem Identification

Louisiana’s tax problems were not a well-kept secret, especially for anyone working in economic development. Though Louisiana looked expensive, it collected relatively little tax revenue thanks to a mix of generous deductions, exemptions, and incentives that together took the state’s effective tax rate from 19th highest in America down to 47th, once we actually got paid. Company CEOs, the media, and the public, however, only saw the high “rack rate,” and presumed that Louisiana is expensive. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve had to explain to a skeptical CFO that Louisiana only looked expensive but was actually cheap…well, I might’ve had more than Louisiana was actually collecting in tax revenue.

The problem was clear: Louisiana’s tax code was overly complicated and a bad sell, and it was costing us companies, jobs, and people.

Our Policy Committee made tax reform a top priority, and our Board — which includes a range of leaders from CEOs, to financial advisors, to small business owners — concurred.

Step 2: Facts & Analysis

GNO, Inc. is a bit old-fashioned, in that we like to start with the facts and then layer on our analysis. It’s just our thing. We use this fact-base both to diagnose the problem and to drive a solution.

Though most public policy is ultimately “sold” through emotional appeal, a solid foundation of empirical data is still essential for any policy’s credibility and success.

Tax Reform Case Study - Facts & Analysis

We discovered two basic facts related to income taxes in Louisiana. First, we confirmed that we looked expensive but were actually cheap. As I said, despite having the 19th highest nominal tax rate, we ended up collecting the 4th least.

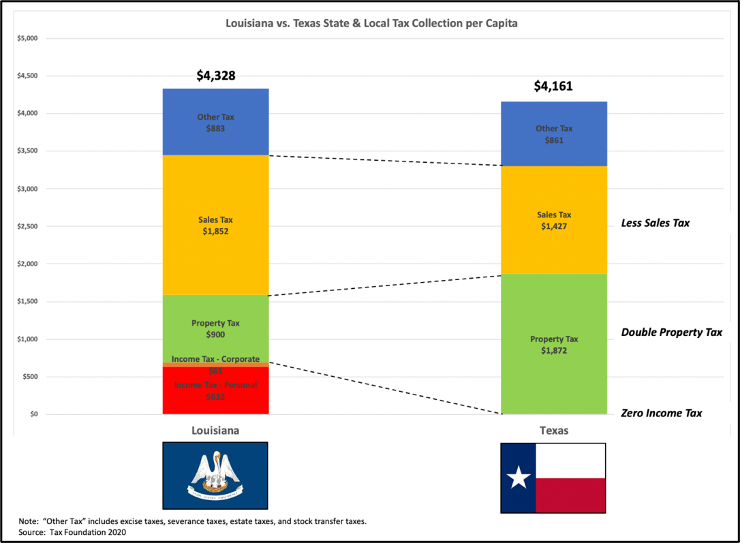

The second fact is that states who have it the other way around—looking cheap, despite collecting as much or more in final taxes—are much more successful at attracting businesses and people. Texas is in fact more expensive than Louisiana for most businesses, and for any individual making less than about $300,000 per year—but no one cares. All they see is the “Zero Income Tax,” and they swoon.

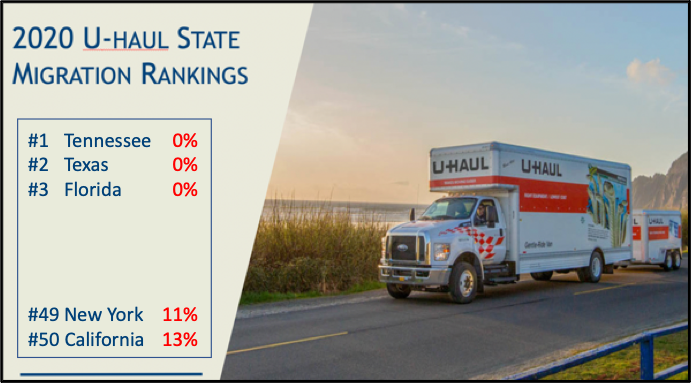

This problem came into stark relief during COVID, when companies and people started fleeing the crowded and expensive coasts in search of more spacious digs. According to U-Haul, which tracks one-way trips with its trucks, the states that lost the most people were New York and California, while the states with the greatest in-migration were Tennessee, Texas, and Florida —all states with no personal income tax. Louisiana, at 6%, was ranked #44. People were literally voting with U-Haul’s fleet.

To underscore the self-defeating nature of Louisiana’s tax structure versus Texas’s, consider the following chart: Louisiana and Texas collect just about the same amount of tax, per capita, but people happily overlook Texas’s double property tax in favor of its zero income tax.

Step 3: Solution Identification

Once you have established a problem and supported it with fact-based analysis, it is time to identify a solution.

One basic decision to make in terms of the solution is whether to go for the Cadillac or the Chevy. (Or, to ask for the Cadillac in hopes of getting a Chevy.) That is, is the better strategy to go for the 100% solution, all at once, or to focus on incremental progress?

In either case, the agreed solution should be “directionally correct” and serve to ameliorate the problem, either immediately or as one step in a longer-term strategy. (Usually, incrementalism is less satisfying, but more realistic and durable.)

Tax Reform Case Study - Solution Identification

For tax reform, the ideal answer (in my opinion) would’ve been the “Texas Model”: look cheap, but actually collect enough taxes—especially local taxes—to fund key services like schools, roads, and safety.

However, moving Louisiana to the Texas Model overnight would mean overturning nearly 100 years of structures and processes built around Louisiana’s low property taxes and high income and sales taxes. This, my friends, was never gonna happen. Imagine your local mayor or assessor telling you they were about to double your property taxes, but it would “all work out for the better.”

So we decided, instead, on an incremental, achievable approach. We wanted to take a step in the right direction, but in the most practical and sustainable way possible. With this approach in mind, we pursued a plan to eliminate deductibility of federal taxes in exchange for a lower income tax rate. Basically, Louisiana was one of only three states in America where taxpayers enjoyed the ability to deduct their paid federal taxes from their Louisiana taxable income—this resulted in a higher nominal tax rate but a lower effective tax rate. We said, How about we just ditch the deduction and give Louisianans a lower tax rate to begin with?

Our goal was to do this in a “revenue neutral” way, such that the state’s taxes would look lower without actually losing the state any money. After some calculation, we determined that we could get rid of the deduction and achieve revenue neutrality with a top personal income tax rate of 4.25% (4th lowest in the nation), down from 6% (25th highest).

As a bonus, Louisiana would be able to step off the “federal tax roller-coaster,” wherein Louisiana’s taxes were inversely affected by taxes from Washington D.C.: with the deduction in place, when federal taxes went up, so did the deduction, and state taxes went down. This lack of control created unpredictability for the Louisiana state treasury. Two birds, one policy stone.

Step 4: Education

Of course, when it comes to public policy, it is not enough to be right. You also have to convince people — in both head and heart — that you are right. This has always been a challenge, for no other reason than because people do not like change. It is even harder today because of the diffusion of media (especially social) and the erosion of trust in government. That being said, with a compelling narrative, and a lot of repetition, it is possible.

Education on legislation can take many forms—media (both earned (e.g., articles) and opinion pieces), advertising, presentations, discussions, and/or lobbying to elected officials—but it has to feel intuitive. People have to just “get” the proposition at a gut level, or they are unlikely to support it. If you’re explaining, you’re losing is an old saying.

The goal of all this education is to generate “political momentum”—a sense of general enthusiasm and near-inevitability about a new bill. Ultimately, you want constituents telling their elected officials how important a piece of legislation is because legislators respond to what they are hearing.

Tax Reform Case Study - Education

In educating people about our tax reform proposal, we needed to convince them that our current system was broken; that our way would be better for them, their families, and their community; and that they could trust us.

To synthesize our thoughts, we developed a pitch deck called “Reform for Louisiana’s Future”. This deck included charts that showed how the current system represented “the worst of both worlds,” making Louisiana look expensive when, in fact, we collected very little tax revenue. The deck also included charts that showed how, for the vast majority of tax payers, the swap would be close to revenue-neutral. (Everyone wants a smarter tax code; they just don’t want to pay more for it.) Finally, the pitch deck included the benefits to Louisiana of the tax swap, including a more attractive environment for companies, more jobs for citizens, and more stable taxes for the state. We took this deck and used it as the basis for countless presentations, interviews, and opinion pieces.

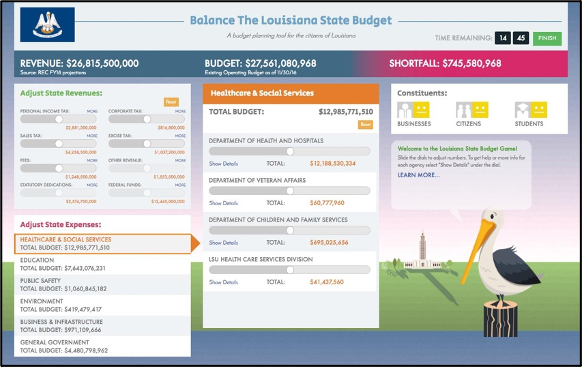

Next, we wanted to do something to add a little sex appeal to the hum-drum issue of tax reform. So, we created an interactive on-line animation, “The Louisiana Tax Game,” that allowed people to play first-hand with the tax code of Louisiana, and see the results for tax-payers and the state. If you made good decisions, the cartoon mascot, “Pelly the Pelican,” smiled. But, if you put the state into deficit, then the poor pelican bled out of her breast, just like on the Louisiana state flag (!).

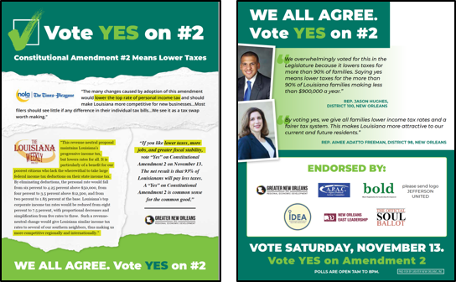

Finally, as the November 2021 constitutional election approached, we developed public advertising materials like yard signs, online ads, and mailers. As tax reform required a constitutional amendment, the people were required to vote, and so we had to appeal to the voting public. Remembering the adage, “If you’re explaining, you’re losing,” we came up with very simple taglines, like “Yes on CA (constitutional amendment) 2 = More Jobs” and “Yes on CA 2 = Lower Taxes” and “Yes on CA 2 = Whiter Teeth.” (We didn’t ultimately use the third one.)

Step 5) The Art of War

“Politics is war without blood,” it has been said. This is true. It is not a meritocracy. Even if you get the analysis, solution, and education right, you can still get ambushed and lose.

So, a critical part of public policy is understanding the opposition—the “enemy,” if you will. Is it strong or weak? Is it organized? Well-funded? What tactics is it likely to use? Answering these questions, and then developing a political war-plan, is essential for policy success.

I don’t particularly like the wargames of politics, and I am not particularly good at them. So I tend to find experts who have the experience, knowledge, and connections to give our team the best advice on approach and tactics. If you want to learn how to invade the Death Star, ask Darth Vader.

Note that the audience for your war exercises will depend on the nature of the legislation, and who has to vote on it. If it is a standard piece of legislation, then the relevant legislators are the primary target, with their voters (who can influence them), as the second target. If, on the other hand, it is a “vote of the people” (as is the case with a constitutional amendment), then you have to go directly to the voters.

Tax Reform Case Study - The Art of War

One of the reasons we chose getting rid of federal deductibility as our means of tax reform is that we thought it was a “constituentless issue.” That is, there was no pre-existing or natural group that would want to go to war to protect the deduction. This lack of organized opposition would make our job much easier.

As we went around selling the idea, we received little specific criticism or push-back. A common theme that did emerge, however, was, “How can we trust government to reduce our income taxes enough to make up for the deduction we are going to lose?” This issue of “trust” was going to be a problem for us because in a low-trust environment (a fair description of American politics today) folks will often prefer the devil they know, to promises from a devil they don’t. We didn’t have a simple way to diffuse the trust issue, as it was just in the civic air.

As the election approached, we were surprised to see some formal, public opposition from a few groups that had previously signaled general support. We felt ambushed by claims like “Constitutional Amendment 2 is a tax give-away for the rich,” which were especially untrue, given that the wealthy—with their larger federal tax burden—benefited the most from the old system.

We discussed three possible responses to the opposition. First, we could do nothing, so as not to add fuel to the fire. Second, we could respond in kind, specifically refuting the allegations. Finally, we could just amp up our own messaging and hope to drown out the noise. We ended up choosing the third strategy and increased our online ads and mailers with messages such as “CA2 = Lower Taxes” and “CA2 = More Jobs.” We kept it as simple and steady as possible: a four-on-the-floor beat, so the people could vote to it.

Finally, as we expected it to be a low-turnout election, we leveraged our network of business members, statewide economic development organizations, and other partners to drive a “turn-out-the-vote” effort.

Tax Reform Case Study – The Result

Constitutional Amendment 2 passed fairly easily, 54% - 46%. We were thrilled, especially because another constitutional amendment related to taxes, CA1, failed. (CA1 failed for two reasons: it generated formal opposition; and the amendment language was confusing to voters).

The Wall Street Journal picked up our victory and wrote a glowing op-ed, giving Louisiana an immediate dose of the positive PR we’d hoped to generate. The Tax Foundation wrote, “These changes have been a long time coming and represent a big step forward for tax reform in Louisiana.”

At GNO, Inc., we described the victory as “One small step for tax rates; one giant leap for tax reform.” Now that we had the taste of tax blood on our teeth, we knew we could look optimistically to further reforms in the future, including sales tax, property tax, and a whole fruitcake of unorthodox taxes, like Louisiana’s inventory tax.

We have lots of work ahead of us, but at least now we have a template for success.

In conclusion, Public Policy is the fundamental way to “change the game,” because it is about changing the rules. Economic development without public policy is economic development on autopilot – it is suboptimized, it is less impactful, and it is certainly less fun.

With this in mind, I strongly encourage economic development professionals and economic development organizations to determine how to play in public policy. It will improve the environment that is essential to economic development success, it will engage your stakeholders, and, if you get it right, it will change the game, for the better.